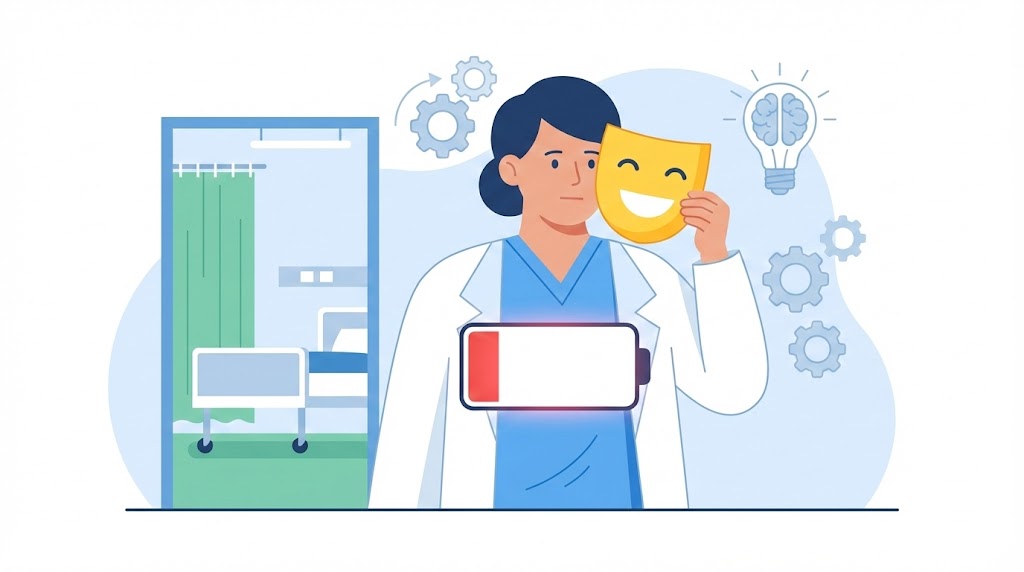

In the modern service industry, particularly in healthcare, the heaviest burden often isn’t the physical exhaustion of a long shift, but the silent, constant pressure to manage one’s feelings. Nurses are expected to be more than just medical practitioners; they are comforters, listeners, and the primary guardians of a patient’s sense of safety. However, the warm smiles and gentle voices we encounter in the corridors don’t always reflect the person’s internal reality. A nurse might be feeling overwhelmed, heartbroken, or bone-tired, yet they must “put on a show” to maintain professional standards. This delicate balancing act is known as Emotional Labor.

Emotional labor involves managing one’s emotions to display expressions that align with workplace expectations, even when those expressions contradict how one actually feels.

Surface Acting vs. Deep Acting

Psychological research, specifically the work of Arlie Hochschild, identifies two distinct ways employees manage this emotional pressure:

- Surface acting: This is when an individual “fakes” an expression, like a polite smile for a difficult supervisor, to reach a work agreement or fulfill a requirement, without changing how they feel inside.

- Deep acting: This is a more profound effort where the individual tries to sincerely feel the emotions expected of them, such as working to find genuine empathy for a patient. While deep acting can be more fulfilling, it is often closely linked to long-term fatigue and stress.

From an HR perspective, this labor is critical because it dictates how employees manage their internal state to remain calm and friendly under pressure. If left unmanaged, it can lead to a sharp decline in motivation, job satisfaction, and overall mental health.

The “Unwritten Emotional Contract”

In the world of industrial relations, emotional labor represents an unwritten emotional contract between the organization and the worker. Companies frequently demand patience and empathy as if these were standard, mechanical job descriptions. Unfortunately, the “emotional cost” of this work is rarely calculated, compensated, or even acknowledged.

However, research in Indonesian organizations suggests that perceived fairness is a game-changer. When nurses feel they are treated fairly by their institution, the heavy demands of emotional labor become much easier to navigate and accept.

A Surprising Paradox: Finding Meaning in the “Mask”

Interestingly, research conducted at the Dr. Amino Gondohutomo Mental Hospital in Semarang found a positive correlation between emotional labor and psychological well-being. The study revealed that the greater the effort nurses made to manage their emotions to help others, the higher their levels of self-acceptance and sense of purpose became.

This suggests that “appearing to be okay” isn’t always a burden. For many, it is a way to find meaning in their profession and experience the inner satisfaction of being truly useful to someone in need. Nevertheless, emotional labor only accounts for about 12.7% of a nurse’s well-being; the rest is shaped by workload, social support, and institutional policies.

Transforming the Burden into Strength

The vital question for HR managers is not whether emotional labor is “good” or “bad,” but how to manage it so it doesn’t become a hidden toxin. To support those who give so much of themselves, organizations should consider:

- Emotional regulation training: Providing programs on deep acting and emotional coping strategies.

- Systematic support: Establishing regular counseling, peer support groups, or “debriefing” sessions after difficult shifts.

- Acknowledge the “emotional cost”: Implementing policies like job rotation in high-pressure units, non-financial rewards for emotional excellence, or even “recovery breaks” to allow workers to reset emotionally.

Conclusion

Emotional labor is not just a job requirement; it is a psychological contract with significant consequences for well-being. By recognizing this “art of pretending” as a legitimate and worthy contribution, organizations can transform emotional masks into meaningful, constructive strengths. When we protect the mental health of our caregivers, we create a more humane and sustainable environment for everyone.